The Changing Paradigm of State-controlled Entities Regulation: Laws, Contracts and Disputes: Introduction

Article from: TDM 6 (2020), in Editorial

Introduction

Jędrzej Górski[1]

The operations of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have increasingly been interwoven with the problem of foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years. On the one hand, the FDI by foreign SOEs have been on the rise. The SOEs domiciled in post-communist states have still been operating under a state-capitalism paradigm instead of pure wealth maximisation paradigm, advancing various non-commercial policy goals of their owners. Such SOEs also have increasingly gone global, investing in a wide range of economic sectors, and stepping into shoes of foreign investors in the host countries. On the other hand, the FDI by foreign investors in the SOEs of the host countries has been on the rise too. SOEs have been increasingly cooperating in domestic operations with foreign investors (including both foreign private enterprises and foreign SCEs) as minority stakeholders, or partners in various forms of public-private-partnership (PPP). This has been particularly the case in the utility and infrastructure sectors, often operating based on special or exclusive rights. While some FDI might be welcome, the host states still prefer to maintain controlling stakes in such sectors.

The emergence of SOEs on the global FDI scene raises broad issues in regulatory fields as diverse as company law, trade law, investment law, competition law or international taxation. Most contentious appear to be laws on investment screening mechanism (ISM) or outright economic sanctions, being newly adopted or amended in many jurisdictions in reply to the challenges identified above. The question of governmental control of multinational companies through ownership clashing with the regulatory autonomy of host states will increasingly lead to many normative conflicts and complex transnational disputes (whether legislative or contractual) which are the focus on this TDM Special Issue.

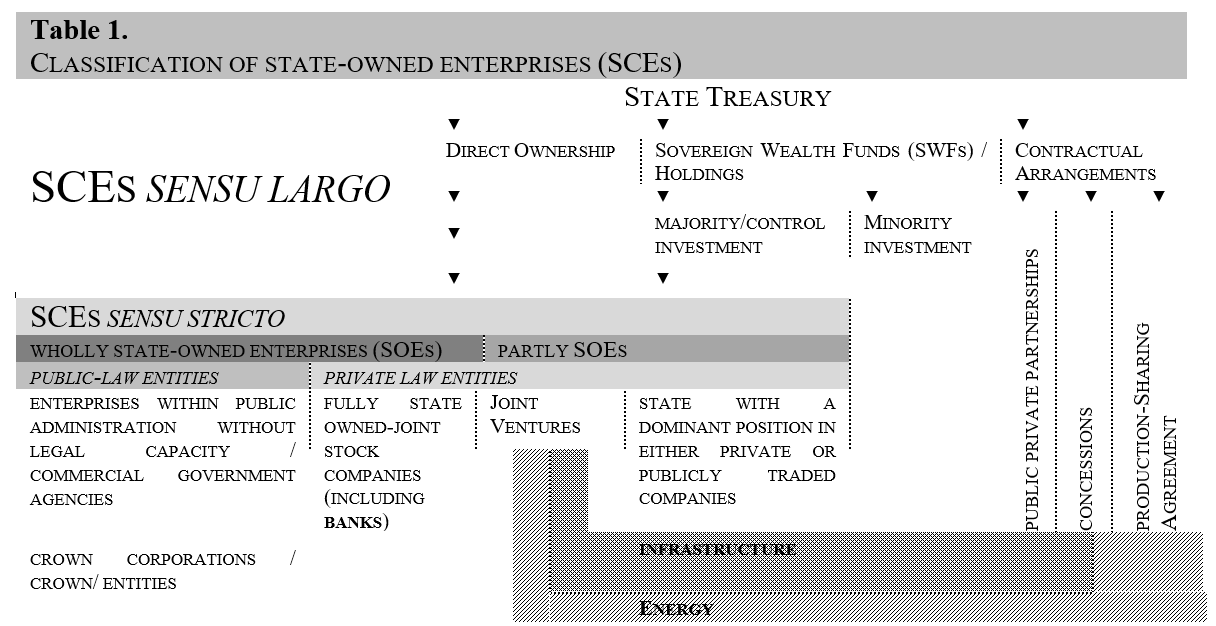

See Jędrzej Górski, 'Global Liberalisation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) as Form of State Controlled Enterprises (SCEs)' (online 22 June 2020) Transnational Dispute Management 1-73, Table 1 in section 22.

SOEs include a broad panoply of entities that have various structures with different degrees of control by states at the central or regional level (Table 1). Governments can exercise control over SOEs through ownership, the right to appoint the management, special-voting-rights, golden shares, or similar instruments. SCEs themselves can be structured as entities without separate legal capacity such as units of public administration carrying out economic activities. They can also be structured as legal entities of public law such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) or crown corporations. For the most part, SOEs are ordinary companies established under private law which are wholly or partly owned by state treasuries, local governments or other state agencies. SOEs also include business organisations controlled by states less directly. The chain of control can be maintained via 1) SWFs or parent holding-SOEs, 2) government licensing especially in the utility sectors, or 3) contractual measures like public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the field of infrastructure and joint-operating-agreements/production sharing agreements (JOAs/PSAs) in the extractive industries. PPPs and JOAs which can but do not need to be structured as separate legal entities. Finally, the control over business organisation by states might also be exercised through the leverage which state-owned banks have over their borrowers.

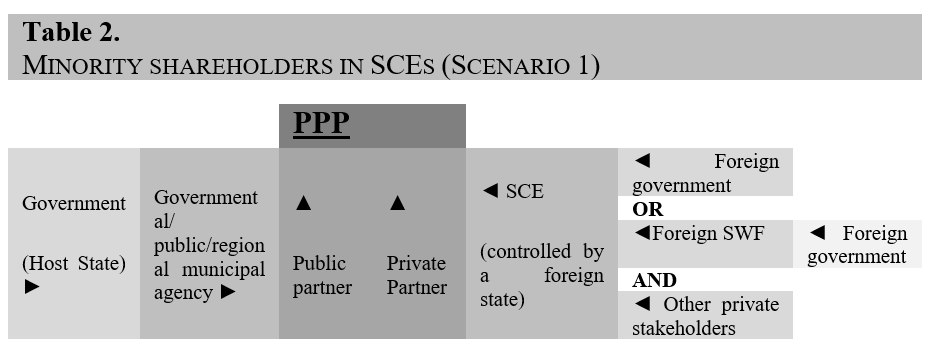

See Jędrzej Górski, 'Global Liberalisation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) as Form of State Controlled Enterprises (SCEs)' (online 22 June 2020) Transnational Dispute Management 1-73, Table 2 in section 22

We might also consider the landscape of minority stakes in SCE, including stakes held by both foreign private and foreign sovereign investors. One could discern two model scenarios in this regard. The first scenario covers newly established and per force relatively small SOEs. The number of minority shareholders in SOEs would be limited to one or a few in the case of newly established joint-ventures between states and private investors. PPPs could also fall under this scenario as a kind of joint ventures between governments and private partners. However, one could find it challenging to determine which partner has a dominant position unless PPPs are established as joint-stock companies rather than contractual arrangements, (see Table 2).

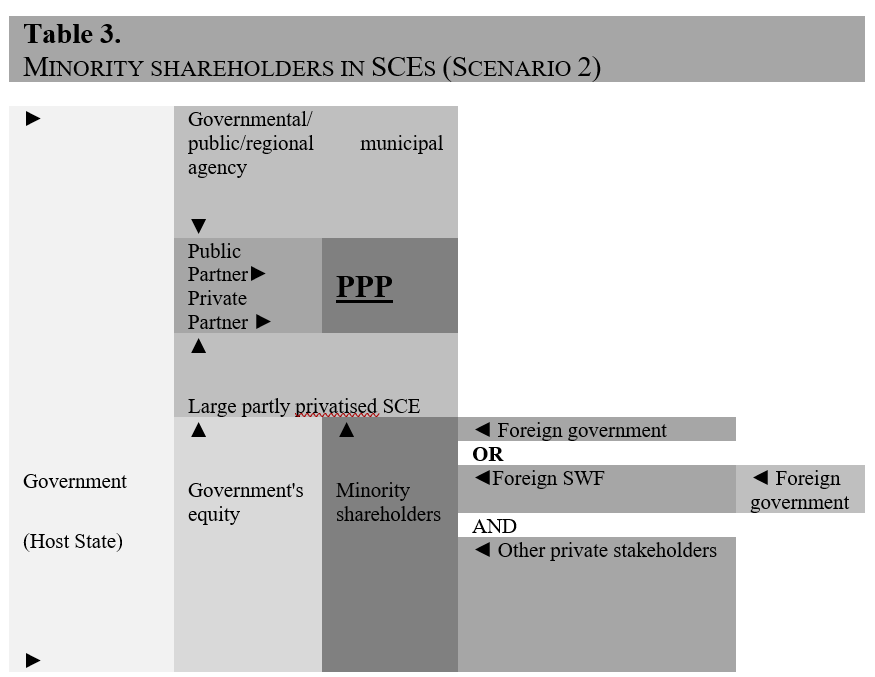

See Jędrzej Górski, 'Global Liberalisation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) as Form of State Controlled Enterprises (SCEs)' (online 22 June 2020) Transnational Dispute Management 1-73, Table 3 in section 22

The second scenario covers the large and well established national champions, which used to be wholly SOEs (Table 3). However, at some point, they have been partially priv atised. Under this scenario, ownership of privatised SOES is split into the unlimited number of minor investors in the stock markets. The rationale behind the privatisation via public offerings instead of selling stakes to one or a few strategic investors is to maintain the effective governmental control over SOEs even with state-owned equity falling below 50%.

As mentioned above, we have identified two broad categories of topics in this research project, including 'investment by SOEs' and 'investment in SOEs.' The problems with investment by SOEs start with issues stemming from the specific legal form of SCEs when acting as investors such as business organisation operating under private/company laws, public-law enterprises, SWFs, or state-controlled banks. They continue with governmental supports of expanding SOEs/SCEs, such as including subsidised/soft loans, equity injections, debt write-offs, export credits (e.g. in violation of the OECD Arrangement on Export Credits), direct governmental grants, preference treatment in terms of access to production factors (commodities and raw material, utilities, land etc.) government procurement, or other forms of subsidies. The problems concerning investment by SOEs also include remedies by host states to anticompetitive practices by foreign State Invested Enterprises (SIEs) like takeover-controls (e.g. by the US Committee on Foreign Investment/CFIUS), countervailing measures (e.g. under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures), competition laws etc. Relevant in this regard also are 1) international instruments addressing business practices of SCEs such as OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises, TPP's chapter on SOEs, or 2) protection of loans granted by state-controlled financial institutions, including concessional loans on the verge of development aid, along with investor/creditor-state and state-state dispute resolutions methods.

The problems with investment in SOEs start with issues stemming from the specific legal form of SOEs when acting as investment recipients, such as gradually privatised SOEs, strategic enterprises, utilities, PPPs, JOAs/PSAs. They continue with the intergovernmental tensions concerning international liberalisation of access to investment in strategic enterprises, utilities, PPPs, JOAs/PSAs. The problems concerning investment in SOEs also include constraints on the participation of foreign investors in privatisations and issues with the privatisation process affecting foreign investors such as continued advancement of non-commercial goals by partly privatised SCEs despite commercialisation. Also relevant in this regard are 1) conditions imposed by the host states on joint ventures with domestic SOEs/SCEs concerning preferences for purchases of domestic content, or forced technology transfers by investors, and 2) stability of fiscal regimes and income/tariffs for foreign investors in business organisations with special rights / concessionaires like utilities, PPPs/JOAs/PSAs along with the protection of foreign investors in such ventures and arbitrability of related-disputes.

In the course of this project running throughout 2019-2020, we have gathered contributions addressing several of the topics mentioned above

1. CHAN Kai-Chieh, in the article titled 'Elephant in the room: On the Notions of SCEs in International Investment Law and International Economic Law,' argues that with the rise of state capitalism, state-controlled enterprises (SCEs) have been evolving. Their activities are becoming more complex, both in terms of ownership, control and their business development strategies. Against this background, the author first argues that international investment law, as it stands now, is insufficiently equipped to deal with the level of structural and managerial flexibility that some SCEs have attained today. While early tribunals have tried to create some bright-line rules concerning the notions relating to SCEs, their efforts eventually prove futile. Given various ambiguities in relevant customary rules, tribunals today seem to rely on an eclectic approach that is highly fact-sensitive, leading to many legal uncertainties and scholarly criticisms. This article proposes two extra-legal tools that can guide future tribunals in their determination of the legal status of SCEs. Firstly, it is submitted that they can invoke relevant rules in international trade law, such as the law of the WTO and other new trade deals applicable between the parties. One the one hand, judicial bodies of the WTO have produced abundant case law concerning the notions of SCE. On the other hand, unlike the majority of early investment treaties, some recent trade deals have addressed to the current state of SCEs. They can be invoked based on Art. 31(3) and Art. 32 of the Vienna Convention on the law of treaties. Secondly, it is submitted that they may refer to national competition rules. These rules can offer more insight into how the entities are treated in their own legal systems. By paying due respect to domestic legal regimes, tribunals can alleviate the concern that international law is unfairly biased against developing States.

2. Carlo de Stefano, in the article titled 'Enhancing the Accountability of SOEs/SCEs in International Economic: Adjudication through Competitive Neutrality,' the authors aims to explore how the principle of competitive neutrality of SOEs or State-controlled enterprises SCEs may be resorted to in international economic litigation, including in the practice of the WTO dispute settlement system (DSS) and investor-State dispute settlement (ISDS). This principle, elaborated initially under the aegis of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), posits that the ownership (either public or private) of a given enterprise should not affect its competitive opportunities in the market arena. SOEs retain a particular vicinity and contact with the public sphere, which is reflected among other things by special benefits under domestic legal systems such as regulatory immunity from antitrust regulation, fiscal advantages or the exemption from bankruptcy legislation. It is submitted that reliance by adjudicators on the principle of competitive neutrality of SOEs/SCEs is desirable to foster the accountability of States and SOEs, also in the eyes of their constituencies, and to level the playing field in markets where SOEs and private undertakings compete.

3. Alexandros Bakos, in the article titled 'When Capital Meets Custom - The Contribution of State-Controlled Enterprises to Customary Investment Law Formation,' argues that when assessing the formation of customary international law (CIL), the adjudicator would usually look at the conduct of a State (alongside evidence of the acceptance of such conduct as law - opinio juris), generally undertaken within a clear governmental, judicial or legislative framework, as the International Law Commission's (ILC) Draft Conclusions on the Identification of Customary Law point out. The author asks then what if the state acts outside the normal confines of formal governmental activity, but the behaviour can still be tied to sovereign interests? Say, state behaviour which is neither clearly governmental nor clearly non-governmental (e.g. commercial). A prominent example in this respect is the behaviour of state- controlled enterprises (SCEs), including when it comes to investment relations/disputes. It is not entirely clear whether the state exercises governmental authority (for example, by seeking to attain various public policy goals other than obtaining profits) or is simply a commercial undertaking like any other profit-oriented enterprise. Forcibly qualifying SCEs as simple commercially-oriented entities ignore the various strategic and security issues associated with them. At the same time, one cannot evade the commercial framework within which such SCEs act. It is also true that the ILC's aforementioned Conclusions exclude the acts of transnational corporations from the scope of behaviour relevant for identifying/expressing CIL. However, the Conclusions did not go in-depth into the nature of these transnational corporations' activities (do they have a governmental nexus or not?). As such, this exclusion cannot be accepted to have an axiomatic value. Moreover, if it can be accepted that, for purposes of state responsibility, the acts of SCEs might be attributed to a host state under customary international law, there are strong arguments for considering such behaviour when identifying customary law. As such, the main question, which the author tackles, is whether SCEs can contribute to the formation/identification of CIL. This can be done either directly when the behaviour or the statement of an SCE is reflective of CIL (e.g. in pleadings before arbitral tribunals), or indirectly ( even if one accepts the ILC's proposition that transnational corporations may not directly contribute to the formation of CIL, they can still indirectly lead to the identification of a CIL).

4. Gianmatteo Sabatino, in the article titled 'The Legal Issues of "Going Global" and the Trans-Nationalisation of the Chinese Public-Private Partnership Model,' asks how does People's Republic of China's (PRC) international cooperation policy deal with the challenges represented both by the underdevelopment issues still affecting Chinese economic law and by the necessity to interact with the different legal system to carry out cooperation projects? The author argues that the PPP model might represent one of the answers. As its diffusion and success within the border of the PRC gradually advances, the Chinese PPP model has also been experiencing an increasing success concerning international cooperation projects, especially within the framework of the Belt & Road initiative (BRI). Though still in its early developing stages, the transnational Chinese PPP already faces up several issues concerning the shaping of a complex and mature legal environment able to support the spread of such a model. The solution to such issues is ultimately aimed at facilitating the "going global" of the Chinese enterprises, in first place SOEs (SOEs). However, it must necessarily stem from the construction of a comprehensive Chinese domestic legal model of PPP, to approach, in second place, the challenge of the development of a transnational PPP model. The author intends to sketch an overview of the issues mentioned above as well as to lay out some possible solutions.

5. Alessandro Spano, in the article titled 'The EU-China Bilateral Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) and the EU Principle of Effective Judicial Protection: Challenges Ahead', discusses the issue of investment arbitration within the context of the EU-China Bilateral Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) and its implications for the protection of the rights of EU investors. The author focuses mainly on the role and status of Chinese SOEs in China's system of governance and economic model to explain the approach of the Chinese government to ISDS mechanisms in the bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Notably, China's socialist market economy is not intended to be an economy free of state regulation. Thus, within the framework of China's system of governance, the market conduct and investment activities of Chinese SOEs assume a symbolic role as they reflect the correlation between China's political and economic processes. Chinese SOEs, with their investment activities, actively contribute to the advancement of China's economic model. Hence, until such an instrumental view of China's economic and investment policies are predominant, any market-access provisions and any types of arbitration mechanisms introduced in BITs will not enjoy an entirely autonomous status. Most likely, these will continue to be regarded as subordinate to policies and rules which are considered by the Chinese government as strategic at a particular time for the promotion of the SOE sector and, ultimately, for the development of the socialist market economy. When considering ISDS mechanisms within the context of EU-China CAI negotiations, many controversies derive from the investment activities of Chinese SOEs in Europe. Here, the already contentious issue of ISDS is enriched by additional concerns depending on the characteristics of Chinese SOEs as potential claimants in investment arbitration procedures.

6. YIN Wei and ZHANG Anran, in the article titled 'Chinese State-Owned Enterprises in Africa: Always a Black-and-White Role?' provides an analysis of the role of Chinese SOEs and their investment in Africa. It aims to help understand the complexity of issues concerning Chinese SOEs and clarify the misconceptions about them. The authors discuss Chinese investment in Africa in general and Chinese SOEs in particular. The concerns and benefits of investment by Chinese SOEs and the impacts of their practice are assessed. The authors explore the regulatory challenges for both China (as the home state of investors) and African countries (as host states of foreign investment). Further action of the Chinese side is examined with a discussion on China's domestic reform and the implication of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The authors argue that for the sustainable development and interests of both sides, the enhanced Sino-African cooperation and the corresponding regulation of Chinese overseas investment are necessary.

7. Gianmatteo Sabatino, in the article titled 'Planning "beside" and "beyond" the State: Multinational as Anthropological Institutions of Global Economic Law,' argues that the role of multinational corporations as market regulators, although commonly accepted among scholars, has rarely be e n assessed from a structural point of view. Corporations, as legal entities, exercise prerogatives, within the global market, that closely resemble, to some extent, those of states. Indeed, their legitimacy and inner hierarchy are founded over the same anthropological and sociological justifications that ensure the functioning of sovereign entities. One of these justifications is undoubtedly the functional approach to economic planning. Economic operators in the corporate form widely employ forms of long-term planning through mechanisms and decision-making processes directly relatable to provisions developed by the most advanced countries in terms of planning law, such as the People's Republic of China. On account of such structural analogy, when corporations and economic entities are state-controlled - more or less directly - a peculiar phenomenon may occur. The State, through formally private economic operators, may pursue long-term development strategies. To do so, it not only exploits the inner management structures of the corporation, but it also lays out regulatory frameworks which often are meant to promote corporations' investments. The purpose of the paper is to briefly sketch some of the main features and issues, from a legal perspective, of this global phenomenon. In the first place, the author discusses the topic from the general point of view of legal anthropology, by defining the role of States and Corporations in the market, to be regarded as a society where the "power" may be either centralised or diffused according to the dynamics in place. In the "society of market" States and Corporations interact with each other, also through long-term planning strategies. Therefore, in the second part of the analysis, the author focuses on the assessment of corporations and state-controlled entities (such as sovereign wealth funds) planning strategies and rules. In particular, it will be pointed out such rules are elaborated, implemented and enforced in a similar way to state plans. In the third and last part of the analysis, the author discusses the legal interaction between States and corporation, by pointing out how States may use a legal instrument to exert their influence over corporations and pursue specific objectives.

8. Andrés Eduardo Alvarado Garzón, in the article titled 'From State-Controlled Enterprises to Investment Screening: Paving the Way for Stricter Rules on Foreign Investment ' argues that SCEs either as SWFs or as SOEs are a rising cause of concern among states receiving their investments. Not only the possib i lity of creating market distortion but also the ties of SCEs with their home state governments arouse distrust in several host states. Although international instruments have been developed to address most of the criticisms of investments made by SCEs, states prefer to rely on domestic regulations. In this context, investment screening laws are becoming more popular in recent years. States avail themselves of concepts such as 'national security' or 'essential security' as a way to preserve the complete autonomy and discretion in designing those laws. Nevertheless, investment screening could go beyond legitimate concerns towards investments of SCEs, leading to undercover economic protectionism.

9. Ondřej Svoboda, in the article titled 'The End of European Naivety: Difficult Times Ahead for SCEs/SOEs Investing in the European Union?', argues that while being open to foreign investment, the European Union has witnessed some new investment trends which have recently raised essential concerns and attracted political and public attention. In particular, the influx of Chinese foreign direct investment by SCEs and SOEs in the EU has triggered a strong call for a screening mechanism in the still decentralised and fragmented EU environment. In response to this changing economic reality, the EU adopted in March 2019 a new regulation, which has entered into force in April 2019. The regulation should provide an answer to the increasing role of non-traditional sources of FDI and safeguard European strategic assets. This change in EU investment policies is motivated by national security concerns, but there is always a risk that it could be used as a protectionist tool in the future. It is to be seen whether the EU can protect its essential security interests as well. The author explores the recent development of screening regulations in the EU and its ramifications for SOEs as well for the broader policy context.

10. Jędrzej Górski, in the article titled 'Global Liberalisation of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) as Form of State Controlled Enterprises (SCEs)' argues that public projects in the field public infrastructure, energy, utilities, or any significant public projects are increasingly outsourced via public-private partnerships (PPPs) and lure multinational enterprises spanning their operations across multiple jurisdictions with varying market entry barriers for foreign investors. The incentives and hindrances to participation in PPPs by such foreign investors could be tied to the level of international liberalisation primarily of government procurement markets, and secondarily of investment and provision of services in heavily-regulated sectors, like utilities. These also rest rests on proper protection of investment by foreign persons, along with the position of such persons in the resolution of controversies that might arise between a public and a private partner. The opening of PPP markets is increasingly addressed in procurement chapters of high-standard regional trade agreements (RTAs) like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). This follows the developments in the World Trade Organization (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) and EU procurement directives whereby PPPs have been gradually incorporated into to coverage of the WTO GPA by the back door, i.e. party-specific schedule of commitments and EU's public-procurement-derived procedural framework has been gradually perfectioned to reflect the complexity of PPPs. The Instruments like the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs) are relevant for the liberalisation of PPPs to the extent that general-commerce freedom of the provision of services and investment by foreign persons in most cases is a prerequisite for access to PPP markets. The related dispute-settlement issues can be differentiated into dispute emerging before and after the conclusion of PPP contractors. Market-access procurement-derived instruments set a framework for the resolution of disputes between potential private partner competing for PPP contracts on the side with contracting authorities (public partners) on the other side. Such instruments also largely secure the stability of PPPs agreement, adding to the investment-protection environment. In turn, the bilateral investment agreements (BITS) investment chapters of RTAs in principle cover PPPs classifiable as a foreign investment despite excluding public procurement from their scope of application expressly.

11. Carlos K.C. Li, in the article titled 'Port and Rail Investments: Reform of Chinese Regulations, Paradigm Shift of Chinese State-Controlled Entities and Global Freedom of Investments,' aims to fill in the gaps of the previous legal research conducted with Prof. Chaisse in 2017. These gaps include the reform on Chinese inbound foreign investment regimes for reciprocal market access of other jurisdictions, the latest corporate practices of SCEs regarding enhancing transparency and accountability and the US and EU's compliance with WTO's GATS Mode 3 and various OECD guidelines. In the context of outbound FDIs in port and rail infrastructures, the author focuses on how Chinese SCEs interact with foreign jurisdictions in respect of freedom of investments and national security. Recently, many host states such as the US and EU adhere to protectionism to counteract Chinese FDIs for the reason of national security or public interest. This act is entirely contrary to freedom of investments conventionally upheld by the global community. In response to this new phenomenon, China has carried out a series of reforms on its regulations in order to create a more favourable environment for its port and rail FDIs. Further, the paradigm of SCEs has started to move towards higher transparency and greater accountability by complying with specific international rules such as IMF's Santiago Principles and OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-owned Enterprises and some private practices. With these paradigm shifts of regulations and SCEs, host states adopt different approaches in response to Chinese port and rail FDIs. The author, in the context of port and rail FDIs, provides an insight into 1) reform of Chinese regulations, 2) paradigm shift of SCEs and 3) global freedom of investments.

12. Joel Slawotsky, in the article titled, 'Global Regulation of State-Owned Enterprises in an Era of Hegemonic Rivalry: The Need to Update Securities Regulations', argues that while the U.S.-China hegemonic rivalry has proximately caused a global tightening of a national security review of investments, overlooked is the incipient rise of economic nationalism and a potential trend of incorporating tenets of state-capitalism. The willingness of market-capitalism practising nations to consider entering capital markets and engaging in cross-border investment is an essential and transformative dynamic with immense implications. At a minimum, dominant or controlling owners, can influence a business to favour the interests of the owner. For private owners, this is acknowledged as focusing on private economic motivations. Sovereign owners may also have other motives aside from profit, such as advancing national objectives. Sovereigns as shareholders are empowered to vote for directors and control corporations, thus potentially substantially influencing and/or controlling another sovereign's political governance, industrial strength and economic future. Share purchases potentially enable control of the "economic/technological high ground". They are effectuated through a method that is generally below the radar without attracting the regulatory attention associated with large transactions or takeovers. Share acquisition can form a stealth stratagem to impact an adversary or obtain valuable information. Therefore, nations should update securities disclosure laws to reflect the transformational developments in emerging technology, both directly and indirectly implicating national security concerns. Foreign governmental entities purchasing shares should be strictly monitored to ensure core economic sectors and emergent technology are protected. The trigger percentage should be lowered for governmental buyers. Legitimate governmental investors should not object to heightened disclosure and reporting requirements

13. Enyinnaya Chimezirim Uwadi, in the article titled 'Challenges of Competition Regulation of State Conducts in Emerging Economies: A Comparative Review of the Case in EU, China and Nigeria', argues that regulation of state conducts and anticompetitive behaviours of SOEs by competition authority could be a very sensitive venture for competition authorities. This is especially the case where the state backs the anticompetitive conducts for the attainment of broader state policy objectives. From a comparative review of the position in EU, China and particularly Nigeria, under the new Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Act 2019, this article identifies the benefits and challenges of regulating state conducts and SOEs anticompetitive activities in emerging markets, and concludes with key recommendations on the way forward.

14. Aleksandr P. Alekseenko, in the article titled 'Restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in State-Controlled Entities under Russian Law', [2] argues that one of the critical priorities of the Russian Government is the attraction of FDI. As a result, foreign investors can enjoy national treatment in Russia, provided they do not threaten state security in any way. The Russian legislation does, however, set some limitations on investments, in particular surrounding companies engaging in business activities of strategic importance. The main aim of these limitations is to supervise transactions of foreign investors, which can lead to their subsequent control over strategic companies. Strategic companies are desirable to foreign capital. This paper analyses the restrictions which apply to foreign investors in Russia. It finds specific features of public supervision of FDI in strategic companies and state-owned entities. It shows problems arising from the procedure of the state's preliminary approval of transactions listed in the Russian legislation. The author concludes that the Russian Government shall increase the transparency of decision making, whereby the Governmental Commission approves FDI in a strategic company and establishes a clear list of transactions, regulated by the Strategic Investments Law.

15. Dini Sejko, in the article titled 'Screening the Investment Screening Mechanism: The Case of Italy and the Belt and Road Initiative', submits that Italy is the first country of the Group of Seven to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in support of the Belt and Road Initiative. The MoU between China and Italy does not create any legal obligation but fosters bilateral relations and creates the expectation of more Chinese investments, mainly from state-controlled enterprises (SCEs), in different economic sectors. Since the Global Financial Crisis foreign SCEs have invested in Italy and other major economies in strategic sectors such as multimodal infrastructure, energy, and high-tech, including artificial intelligence and 5G network. The Italian authorities have addressed domestic national security concerns and modified the investment screening mechanism (ISM) legislation expanding the governmental power to examine and block foreign investments. The author examines the evolution and sophistication of the Italian ISM. Initially, the author examines the language of the Italian ISM and its function in light of significant acquisitions by SCEs in strategic economic sectors, and the power of the government to exclude certain SCEs from investing in specific sectors. Then the author focuses on the significance of the European Union ISM established in 2019 and impact on the Italian domestic legislation as a Member State of the European Union. The last part of the article analyses the relevance of the protections of the China Italy bilateral investment treaty. The author discusses if Chinese SCEs can use the bilateral investment treaty protections to react to potential discriminatory treatment due to national security risks, and bring investment claims against Italy.

16. Maria Lucia L. M. Padua Lima and Paulo Clarindo Goldschmidt, in the article titled 'Brazilian Car Wash Operation: Petrobras Case', examine the case of Petróleo Brasileiro SA (Petroleum of Brazil -Petrobras) the largest mixed capital Brazilian company. Founded in 1953, the company is currently the focus of significant corruption investigations in the so-called Car Wash Operation. The severe crisis caused by the systemic corruption that affected Petrobras has created a domino effect within the whole oil and gas extraction and production chain in Brazil that led to the contagion effect in the entire Brazilian economy. To illustrate the systemic corruption developed in Petrobras during the years of the PT governments (2003-2016), the author talks about cases such as Pasadena (onshore operation) and Sete Brasil (offshore operation). Besides these two emblematic cases, many others occurred during the PT period. The common ground of all these cases is the determination to use Petrobras to corrupt the Brazilian democratic institutions without neglecting the personal enrichment of the superiors. On the other hand, Petrobras was not the only company to suffer the abuses of PT's mismanagement.